In Lübeck, Germany, on March 6, 1981.

Marianne Bachmeier stepped into the courtroom with a composed yet determined air. Little did anyone know that the events about to unfold would send shockwaves through society, leaving an indelible mark for decades. Hidden in her handbag was a small, loaded pistol, and her target was Klaus Grabowski, the man accused of abducting, abusing, and murdering her seven – year – old daughter, Anna. In a matter of seconds, she fired seven shots, and Grabowski’s life ended on the courtroom floor.

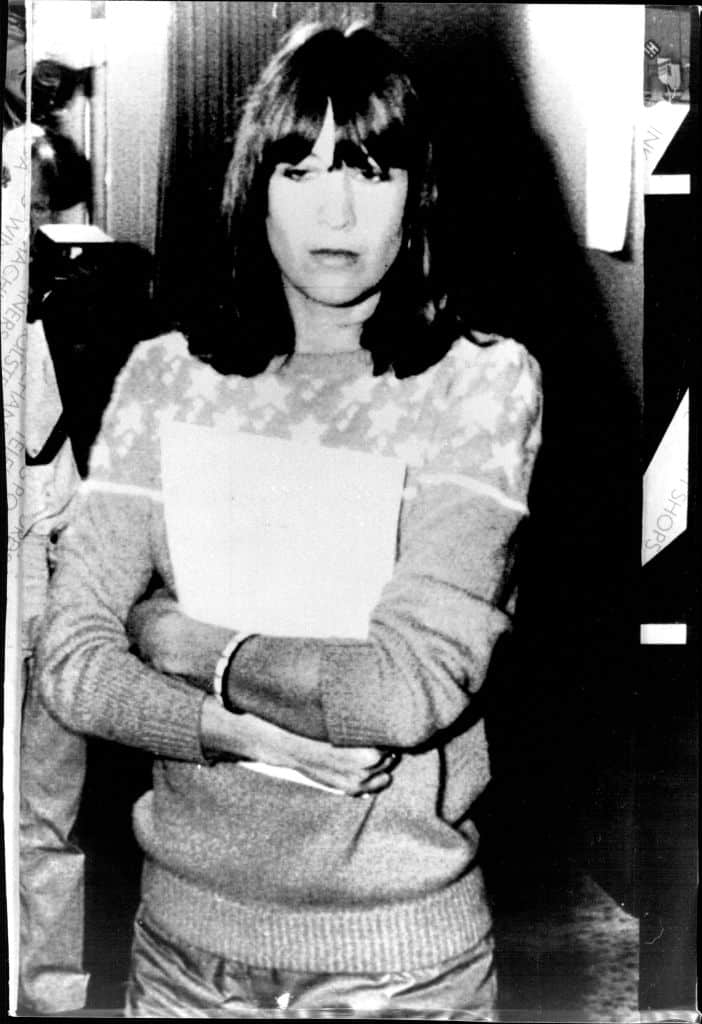

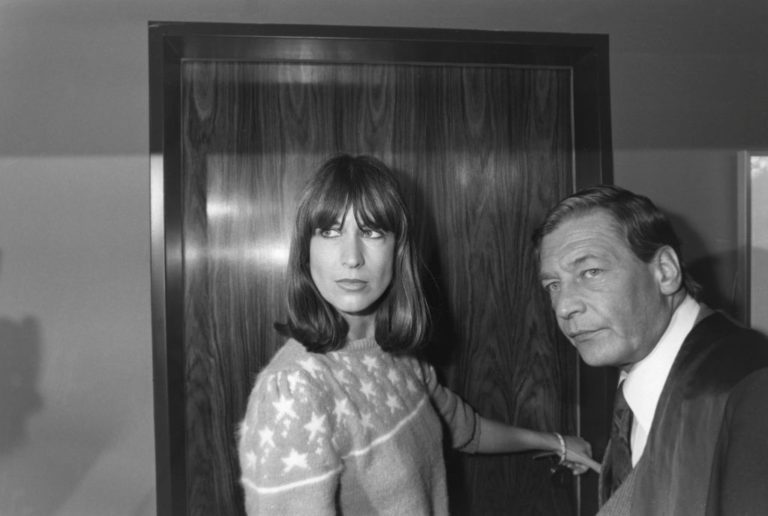

Arrested immediately, Marianne showed no remorse. She had done what many parents might secretly consider in their darkest moments – seeking her own brand of justice. Her actions, raw and driven by emotion, ignited a global debate. Even forty years later, the name Marianne Bachmeier still stands as a symbol of revenge, grief, and the blurred boundaries between legitimate justice and taking the law into one’s own hands.

Marianne’s life was filled with hardships from the start. Her childhood was overshadowed by tragedy, trauma, and deep emotional wounds. Her father’s service in the Waffen – SS during Nazi Germany cast a long shadow over the family. As a young girl, Marianne endured abuse and trauma. At sixteen, she became pregnant and gave her baby up for adoption. Two years later, she faced the same heart – rending decision. But in 1973, when she gave birth to Anna, everything changed. This time, she kept the child and raised her as a single mother.

Anna was described by everyone as a bright and kind – hearted little girl, full of curiosity and energy. She lived with her mother in Lübeck, and Marianne worked hard at a small pub to make ends meet. Life was difficult, but their bond was unbreakable. That bond was brutally shattered on May 5, 1980. After a minor argument at home, Anna disappeared. She decided to skip school and visit a friend but never arrived. On her way, 35 – year – old Klaus Grabowski, a convicted sex offender with a history of molesting two other young girls, lured and kidnapped her.

Grabowski, who lived nearby, had a history of violence and manipulation. While serving time for his previous crimes, he had voluntarily undergone chemical castration. Later, he received hormone therapy in an attempt to lead a “normal” life. At the time of Anna’s murder, he was living with his fiancée and had re – entered the community with little scrutiny, despite his troubled past. He held Anna captive in his apartment for several hours, during which he abused her and finally strangled her to death.

He placed Anna’s tiny body in a cardboard box and left it by a canal. Later that day, Grabowski returned to move and bury her, but his fiancée, who discovered the crime, called the police. He was arrested that same night at a local bar.

Grabowski’s arrest did little to soothe Marianne’s pain. During his trial, he made disturbing claims, alleging that Anna had tried to seduce and blackmail him. This only added to Marianne’s suffering. Already grieving the loss of her daughter, she now had to endure her child being slandered in court.

On the morning of March 1981, on the third day of the trial, Marianne entered the courtroom with a pistol hidden in her handbag. As the trial was about to begin, she stood up, pulled out the gun, and fired seven shots at Grabowski. He died instantly. Her words were clear and full of purpose: “He killed my daughter… I wanted to shoot him in the face, but I shot him in the back… I hope he’s dead.” Witnesses, including police officers, remembered her calling him a “pig” right after the shooting.

She was quickly arrested. Initially charged with murder, she went on trial the following year. She claimed to have been in a trance – like state, triggered by seeing her daughter’s image in the courtroom. However, investigators found evidence to the contrary. Her familiarity with the gun and the precision of her actions suggested premeditation. In a handwriting sample during a psychological evaluation, she wrote, “I did it for you, Anna,” along with seven hearts, one for each year of her daughter’s life.

The trial became a media spectacle. Many Germans saw her as a tragic hero, a mother pushed to the limit. Others were more critical, arguing that justice should always be left to the courts, no matter how heinous the crime. The press, which was initially sympathetic, started to dig into her past. They talked about her troubled youth, her time working at the bar, and the babies she had given up for adoption. Public opinion became sharply divided.

In the end, Marianne was found guilty of premeditated manslaughter and illegal possession of a firearm. She was sentenced to six years in prison but was released after only three years. A national survey showed the public’s ambivalence about her punishment.